Data breach

A data breach, also known as data leakage, is "the unauthorized exposure, disclosure, or loss of personal information".[1] Since the advent of data breach notification laws in 2005, reported data breaches have grown dramatically.

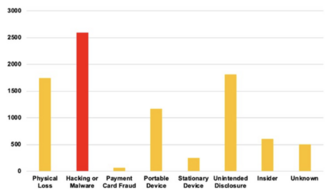

Data breaches are most commonly caused either by a targeted cyberattack, an opportunistic attack, or inadvertent information leakage. Attackers have a variety of motives, from financial gain to political activism, political repression, and espionage. There are several technical root causes of data breaches, including accidental disclosure of information, lack of encryption, malware, phishing, and software vulnerabilities. Although prevention efforts by the company holding the data can reduce the risk of data breach, it cannot bring it to zero.

A large number of data breaches are never detected. If a breach made known to the company holding the data, post-breach efforts commonly include containing the breach, investigating its scope and cause, and notifications to people whose records were compromised, as required by law in many jurisdictions. Law enforcement agencies may investigate breaches, although the hackers responsible are rarely caught.

Many criminals sell data obtained in breaches on the dark web. Thus, people whose data was compromised are at elevated risk of identity theft for years afterwards and a significant number will become victims of this crime. Lawsuits against the company that was breached are common, although few victims receive money from them. The company may suffer lost business or reputational damage, and incur expenses due to the breach and subsequent lawsuits.

Definition[edit]

A data breach is a violation of "organizational, regulatory, legislative or contractual" law or policy[2] that causes "the unauthorized exposure, disclosure, or loss of personal information".[1] Legal and contractual definitions vary.[3][2] Some researchers include other types of information, for example intellectual property or classified information.[4] However, companies mostly disclose breaches because it is required by law,[5] and only personal information is covered by data breach notification laws.[6][7]

History and prevalence[edit]

Before the widespread adoption of data breach notification laws around 2005, the prevalence of data breaches is difficult to determine. Even afterwards, statistics per year cannot be relied on because data breaches may be reported years after they occurred,[8] or not reported at all.[9] Nevertheless, the statistics show a continued increase in the number and severity of data breaches that continues as of 2022[update].[10] In 2016, researcher Sasha Romanosky estimated that data breaches outnumbered other security breaches by a factor of four.[11]

The 2005 ChoicePoint data breach—caused by fraudsters posing as legitimate customers of the Big Data firm ChoicePoint, who obtained information on around 162,000 people—was one of the first to be publicly reported.[8] Following additional revelations about breaches of several companies, particularly the 2005 CardSystems Solutions data breach, legislatures around the United States began to pass laws requiring notification about breaches when an individual's data was compromised.[12] In the 2000s, the dark web—parts of the internet where it is difficult to trace users and illicit activity is widespread—began to be set up, increasing in the 2010s with the advent of untraceable cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. Information obtained in data breaches is often offered for sale there.[13] In 2012, ransomware—a type of malware that encrypts data storage, so that hackers can demand a ransom for a decryption key—saw an increase in popularity.[14] Around the 2016 United States presidential election, there was an increase in data breaches for political gain.[15]

Perpetrators[edit]

According to a 2020 estimate, 55 percent of data breaches were caused by organized crime, 10 percent by system administrators, 10 percent by end users such as customers or employees, and 10 percent by states or state-affiliated actors.[16] Opportunistic criminals may cause data breaches—often using malware or social engineering attacks, but they will typically move on if the security is above average. More organized criminals have more resources and are more focused in their targeting of particular data.[17] Both of them sell the information they obtain for financial gain.[18] Another source of data breaches are politically motivated hackers, for example Anonymous, that target particular objectives.[19] State-sponsored hackers target either citizens of their country or foreign entities, for such purposes as political repression and espionage. Often they use undisclosed zero-day vulnerabilities for which the hackers are paid large sums of money.[20]

Criminals often communicate with each other using the dark web, such as .onion or I2P.[21] After a data breach, criminals make money by selling data, such as usernames, passwords, social media or customer loyalty account information, debit and credit card numbers,[18] and personal health information (see medical data breach).[22] This information may be used for a variety of purposes, such as spamming, obtaining products with a victim's loyalty or payment information, identity theft, prescription drug fraud, or insurance fraud.[23] The threat of data breach or revealing information obtained in a data breach can be used for extortion, often using ransomware technology (where the criminal demands a payment in exchange for not activating malicious software).[22]

Causes[edit]

Authors Neil Daswani and Moudy Elbayadi list six technical root causes that account for most breaches:[24]

- The majority of data breaches could have been averted by storing all sensitive information in an encrypted format. That way, physical possession of the storage device cannot grant access to the information contained within unless the attacker also has the encryption key.[25]

- Phishing is a method of obtaining a user's credentials by sending them a malicious message impersonating a legitimate entity, such as a bank, and getting the user to enter their credentials onto a malicious website controlled by the cybercriminal. Two-factor authentication can prevent the malicious actor from using the credentials.[26]

- Malware (malicious software) is a common cause of breaches. Some malware is downloaded by users via clicking on a malicious link, but it is also possible for malicious web applications to download malware just from visiting the website. Keyloggers, a type of malware that records a user's keystrokes, are often used in data breaches.[27]

- Many data breaches occur on the hardware operated by a partner of the organization targeted—including the 2013 Target data breach and 2014 JPMorgan Chase data breach.[28] Outsourcing work to a third party leads to a risk of data breach if that company has lower security standards; in particular, small companies often lack the resources to take as many security precautions.[29][28] As a result, outsourcing agreements often include security guarantees and provisions for what happens in the event of a data breach.[29]

- Software vulnerabilities—security faults that can be exploited by an attacker—also are a major source of data breaches.[30][31] Both software written by the target of the breach and third party software used by them are vulnerable to attack.[30] Patches are often released to fix identified vulnerabilities, but those that remain unknown (zero days) as well as those that have not been patched are still liable for exploitation.[32]

- Another source of breaches is accidental disclosure of information, for example publishing information that should be kept private.[33][34] With the increase in remote work and bring your own device policies, large amounts of corporate data is stored on personal devices of employees. Via carelessness or disregard of company security policies, these devices can be lost or stolen.[35] Technical solutions can prevent many causes of human error, such as encrypting all sensitive data, preventing employees from using insecure passwords, installing antivirus software to prevent malware, and implementing a robust patching system to ensure that all devices are kept up to date.[36]

Although attention to security can reduce the risk of data breach, it cannot bring it to zero. Security is not the only priority of organizations, and an attempt to achieve perfect security would make the technology unusable.[37]

Breach lifecycle[edit]

Prevention[edit]

Beyond protecting a firm from the consequences of a breach, security has other benefits—for example, it can help to sell its products.[38] To prioritize security against data breaches, authors Neil Daswani and Moudy Elbayadi recommend hiring a chief information security officer (CISO) that reports to the CEO, and empowering that individual with sufficient funding and resources.[39] They recommend examining similar organizations to help determine funding levels, but caution that above-average funding may be necessary to achieve better than average security.[40] Funding, in their opinion, should be prioritized for addressing the technical root causes of data breaches.[41] They argue that paranoia[42] and proactive action to increase security is cheaper and more effective than last-minute or reactive actions,[43] and propose ongoing training[44] and networking with security professionals, information sharing with other organizations facing similar threats.[45] Defense measures can include an updated incident response strategy, contracts with digital forensics firms that could investigate a breach,[46] cyber insurance,[47][7] and monitoring the dark web for stolen credentials of employees.[48]

The architecture of a company's systems plays a key role in deterring attackers. Daswani and Elbayadi recommend having only one means of authentication,[49] avoiding redundant systems, and making the most secure setting default.[50] Giving employees and software the least amount of access necessary to fulfill their functions (principle of least privilege) limits the likelihood and damage of breaches.[49][51] Several data breaches were enabled by reliance on security by obscurity; the victims had put access credentials in publicly accessible files.[52] Nevertheless, prioritizing ease of use is also important because otherwise users might circumvent the security systems.[53] Rigorous software testing, including penetration testing, can reduce software vulnerabilities, and must be performed prior to each release even if the company is using a continuous integration/continuous deployment model where new versions are constantly being rolled out.[54]

Avoiding the collection of data that is not necessary and destruction of data that is no longer necessary can mitigate the harm from breaches.[55][56][57]

Response[edit]

A large number of data breaches are never detected.[58] Of those that are, most breaches are detected by third parties;[59][60] others are detected by employees or automated systems.[61] Responding to breaches is often the responsibility of a dedicated computer security incident response team, often including technical experts, public relations, and legal counsel.[62][63] Many companies do not have sufficient expertise in-house, and subcontract some of these roles;[64] often, these outside resources are provided by the cyber insurance policy.[65] After a data breach becomes known to the company, the next steps typically include confirming it occurred, notifying the response team, and attempting to contain the damage.[66]

To stop exfiltration of data, common strategies include shutting down affected servers, taking them offline, patching the vulnerability, and rebuilding.[67] Once the exact way that the data was compromised is identified, there is typically only one or two technical vulnerabilities that need to be addressed in order to contain the breach and prevent it from reoccurring.[68] A penetration test can then verify that the fix is working as expected.[69] If malware is involved, the organization must investigate and close all infiltration and exfiltration vectors, as well as locate and remove all malware from its systems.[70] If data was posted on the dark web, companies may attempt to have it taken down.[71] Containing the breach can compromise investigation, and some tactics (such as shutting down servers) can violate the company's contractual obligations.[72] After the breach is fully contained, the company can then work on restoring all systems to operational.[73]

Gathering data about the breach can facilitate later litigation or criminal prosecution,[74] but only if the data is gathered according to legal standards and the chain of custody is maintained.[75] Database forensics can narrow down the records involved, limiting the scope of the incident.[76] Extensive investigation may be undertaken, which can be even more expensive that litigation.[60] In the United States, breaches may be investigated by government agencies such as the Office for Civil Rights, the United States Department of Health and Human Services, and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).[77] Law enforcement agencies may investigate breaches[78] although the hackers responsible are rarely caught.[79]

Notifications are typically sent out as required by law.[80] Many companies offer free credit monitoring to people affected by a data breach, although only around 5 percent of those eligible take advantage of the service.[81] Issuing new credit cards to consumers, although expensive, is an effective strategy to reduce the risk of credit card fraud.[81] Companies try to restore trust in their business operations and take steps to prevent a breach from reoccurring.[82]

Consequences[edit]

Estimating the cost of data breaches is difficult, both because not all breaches are reported and also because calculating the impact of breaches in financial terms is not straightforward. There are multiple ways of calculating the cost, especially when it comes to personnel time dedicated to dealing with the breach.[83] Author Kevvie Fowler estimates that more than half the direct cost incurred by companies is in the form of litigation expenses and services provided to affected individuals, with the remaining cost split between notification and detection, including forensics and investigation. He argues that these costs are reduced if the organization has invested in security prior to the breach or has previous experience with breaches. The more data records involved, the more expensive a breach typically will be.[84]

In 2016, researcher Sasha Romanosky estimated that while the mean breach cost around $5 million, this figure was inflated by a few highly expensive breaches, such as those targeting Target, Sony, Anthem, and Home Depot. The typical data breach was much less costly, around $200,000, although many companies suffered multiple breaches, driving up costs. Romanosky estimated the total annual cost in the United States to be around $10 billion.[85] Impacts on the company can range from lost business, reduced employee productivity due to systems being offline or personnel redirected to working on the breach,[86] resignation or firing of senior executives, decline in stock price,[77] reputational damage,[77][87] and increasing future cost of auditing or security.[77] However, most consumers affected by a data breach continue to do business with the company and sales may not decline.[88]

Most data breaches target personal data.[89] Consumers may suffer various forms of tangible or intangible harm from the theft of their personal data, or not notice any harm.[90] A significant portion of those affected by a data breach become victims of identity theft. Due to increased remediation efforts in the United States after 2014, this risk decreased significantly from one in three to one in seven.[81] A person's identifying information often circulates on the dark web for years, causing an increased risk of identity theft regardless of remediation efforts.[79][91] Even if a customer does not end up footing the bill for credit card fraud or identity theft, they have to spend time resolving the situation.[89][92] Intangible harms include doxxing (publicly revealing someone's personal information), for example medication usage or personal photos.[93]

Laws[edit]

Notification[edit]

The law regarding data breaches is often found in legislation to protect privacy more generally, and is dominated by provisions mandating notification when breaches occur.[94] Laws differ greatly in how breaches are defined,[3] what type of information is protected, the deadline for notification,[6] and who has standing to sue if the law is violated.[95] Notification laws increase transparency and provide an reputational incentive for companies to reduce breaches.[96] The cost of notifying the breach can be high if many people were affected and is incurred regardless of the company's responsibility, so it can function like a strict liability fine.[97]

In 2018, the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) took effect. The GDPR requires notification within 72 hours, with very high fines possible for large companies not in compliance. This regulation also stimulated the tightening of data privacy laws elsewhere.[98][99] As of 2022[update], the only United States federal law requiring notification for data breaches is limited to medical data regulated under HIPAA. Beginning with California in 2005, all 50 states have passed their own general data breach notification laws.[99]

Security safeguards[edit]

Measures to protect data from a breach are typically absent from the law or vague, in contrast to the more concrete requirements found in cybersecurity law.[94] Filling this gap is standards required by cyber insurance, which is held by most large companies and functions as de facto regulation.[100][101] Of the laws that do exist, there are two main approaches—one that prescribes specific standards to follow, and the reasonableness approach.[102] The former is rarely used due to a lack of flexibility and reluctance of legislators to arbitrate technical issues; with the latter approach, the law is vague but specific standards can emerge from case law.[103] Companies often prefer the standards approach for providing greater legal certainty, but they might check all the boxes without providing a secure product.[104] An additional flaw is that the laws are poorly enforced, with penalties often much less than the cost of a breach, and many companies do not follow them.[105]

Litigation[edit]

Many class-action lawsuits, derivative suits, and other litigation have been brought after data breaches.[106] They are often settled regardless of the merits of the case due to the high cost of litigation.[107][108] Even if a settlement is paid, few affected consumers receive any money as it usually is only cents to a few dollars per victim.[77][108] Legal scholars Daniel J. Solove and Woodrow Hartzog argue that "Litigation has increased the costs of data breaches but has accomplished little else."[109] Plaintiffs often struggle to prove that they suffered harm from a data breach.[109] The contribution of a company's actions to a data breach varies,[105][110] and likewise the liability for the damage resulting for data breaches is a contested matter. It is disputed what standard should be applied, whether it is strict liability, negligence, or something else.[110]

See also[edit]

- Full disclosure (computer security)

- Medical data breach

- Surveillance capitalism

- Data breaches in India

References[edit]

- ^ a b Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 5.

- ^ a b Fowler 2016, p. 2.

- ^ a b Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 41.

- ^ Shukla et al. 2022, pp. 47–48.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, p. 18.

- ^ a b Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 42.

- ^ a b Fowler 2016, p. 45.

- ^ a b Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 18.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 29.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, pp. 17–18.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, p. 9.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 19.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 21.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 23.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 26.

- ^ Crawley 2021, p. 46.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Fowler 2016, p. 13.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Fowler 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 13.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 15.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 16–19.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 19–22.

- ^ a b Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Fowler 2016, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 25.

- ^ Seaman 2020, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 28.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 19.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 7, 9–10.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 11.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 206.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 198.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 205.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 206–207.

- ^ a b Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 217.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Lenhard 2022, p. 53.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, p. 218.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Daswani & Elbayadi 2021, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Lenhard 2022, p. 60.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 184.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 146.

- ^ Crawley 2021, p. 39.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 64.

- ^ a b National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, p. 25.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Crawley 2021, p. 97.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 5, 32.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 86.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 94.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 115.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 116.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 119.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 124.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 188.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 83.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d e National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, p. 22.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 44.

- ^ a b Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 58.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 5, 44.

- ^ a b c National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, p. 13.

- ^ Fowler 2016, pp. 5–6.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 21.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, p. 10.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 22.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 41.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, pp. 14, 18.

- ^ a b National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, p. 29.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, p. 27.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 56.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, pp. 27–29.

- ^ a b Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 10.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 43.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 44.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 45.

- ^ Seaman 2020, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 40.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, p. 24.

- ^ Talesh 2018, p. 237.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 48.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 52.

- ^ a b Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 53.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Fowler 2016, p. 222.

- ^ a b Solove & Hartzog 2022, pp. 55, 59.

- ^ a b Solove & Hartzog 2022, p. 55.

- ^ a b National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2016, p. 23.

Sources[edit]

- Crawley, Kim (2021). 8 Steps to Better Security: A Simple Cyber Resilience Guide for Business. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-81124-4.

- Daswani, Neil; Elbayadi, Moudy (2021). Big Breaches: Cybersecurity Lessons for Everyone. Apress. ISBN 978-1-4842-6654-0.

- Fowler, Kevvie (2016). Data Breach Preparation and Response: Breaches are Certain, Impact is Not. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-12-803451-4.

- Lenhard, Thomas H. (2022). Data Security: Technical and Organizational Protection Measures against Data Loss and Computer Crime. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-658-35494-7.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2016). "Forum on Cyber Resilience Workshop Series". Data Breach Aftermath and Recovery for Individuals and Institutions: Proceedings of a Workshop. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-44505-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Seaman, Jim (2020). PCI DSS: An Integrated Data Security Standard Guide. Apress. ISBN 978-1-4842-5808-8.

- Shukla, Samiksha; George, Jossy P.; Tiwari, Kapil; Kureethara, Joseph Varghese (2022). Data Ethics and Challenges. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-981-19-0752-4.

- Solove, Daniel J.; Hartzog, Woodrow (2022). Breached!: Why Data Security Law Fails and How to Improve it. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-094057-7.

- Talesh, Shauhin A. (2018). "Data Breach, Privacy, and Cyber Insurance: How Insurance Companies Act as "Compliance Managers" for Businesses". Law & Social Inquiry. 43 (02): 417–440. doi:10.1111/lsi.12303.