Academic library

An academic library is a library that is attached to a higher education institution and serves two complementary purposes: to support the curriculum and the research of the university faculty and students.[1] It is unknown how many academic libraries there are worldwide. An academic and research portal maintained by UNESCO links to 3,785 libraries. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, there are an estimated 3,700 academic libraries in the United States.[1] In the past, the material for class readings, intended to supplement lectures as prescribed by the instructor, has been called reserves. Previously before the electronic appliances became available, the reserves were supplied as actual books or as photocopies of appropriate journal articles. Modern academic libraries generally also provide access to electronic resources.

Academic libraries must determine a focus for collection development since comprehensive collections are not feasible. Librarians do this by identifying the needs of the faculty, student body, the mission and academic programs of the college or university. When there are particular areas of specialization in academic libraries, these are often referred to as niche collections. These collections are often the basis of a special collection department and they may include original papers, artwork, and artifacts written or created by a single author or about a specific subject.

There is a great deal of variation among academic libraries based on their size, resources, collections, and services. The Harvard University Library is considered to be the largest strict academic library in the world,[2] although the Danish Royal Library—a combined national and academic library—has a larger collection.[3] Another notable example is the University of the South Pacific which has academic libraries distributed throughout its twelve member countries.[1] The University of California operates the largest academic library system in the world, managing more than 40.8 million print volumes across 100 libraries on ten campuses.[4]

History[edit]

Libraries date back to the ancient world, notably the Library of Alexandria and the historically famous Library of Nalanda University, which apparently burned for months because of the sheer number of manuscripts.[5]

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2017) |

United States[edit]

The first colleges in the United States were intended to train clergy members. The libraries associated with these institutions largely consisted of donated books on the subjects of theology and the classics. In 1766, Yale had approximately 4,000 volumes, second only to Harvard.[6] Access to these libraries was restricted to faculty members and a few students: the only staff was a part-time faculty member or the president of the college.[7] The priority of the library was to protect the books, not to allow patrons to use them. In 1849, Yale was open 30 hours a week, the University of Virginia was open nine hours a week, Columbia University four, and Bowdoin College only three.[8] Students instead created literary societies and assessed entrance fees for building a small collection of usable volumes, often over what the university library held.[8]

Around the turn of the century, this approach began to change. The American Library Association (ALA) was formed in 1876, with members including Melvil Dewey and Charles Ammi Cutter. Libraries re-prioritized to improve access to materials and found funding increasing due to increased demand for said materials.[9]

Academic libraries today vary regarding the extent to which they accommodate those not affiliated with their parent universities. Some offer reading and borrowing privileges to members of the public on payment of an annual fee; such fees can vary greatly. The benefits usually do not extend to such services as computer usage other than to search the catalog or Internet access. Alumni and students of cooperating local universities may be given discounts or other considerations when arranging for borrowing privileges. On the other hand, some universities' libraries are restricted to students, faculty, and staff. Even in this case, they may make it possible for others to borrow materials through interlibrary loan programs.

Libraries of land-grant universities generally are more accessible to the public. In some cases, they are official government document repositories and are required to be open to the public. Still, public members are generally charged fees for borrowing privileges and usually are not allowed to access everything they would be able to as students.

Canada[edit]

Academic libraries in Canada are relatively recent relative to other countries. The first academic library in Canada was opened in 1789 in Windsor, Nova Scotia.[10] Academic libraries were significantly small during the 19th century and up until the 1950s, when Canadian academic libraries began to grow steadily as a result of greater importance being placed on education and research.[10] The growth of libraries throughout the 1960s was a direct result of many overwhelming factors, including inflated student enrollments, increased graduate programs, higher budget allowance, and general advocacy of the importance of these libraries.[11] As a result of this growth and the Ontario New Universities Library Project that occurred during the early 1960s, five new universities were established in Ontario that all included fully cataloged collections.[10] The establishment of libraries was widespread throughout Canada and was furthered by grants provided by the Canada Council and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, which sought to enhance library collections.[10] Since many academic libraries were constructed after World War II, a majority of the Canadian academic libraries that were built before 1940 that had not been updated to modern lighting, air conditioning, etc., are either no longer in use or are on the verge of decline.[12] The total number of college and university libraries increased from 31 in 1959–1960 to 105 in 1969–1970.[13]

Following the growth of academic libraries in Canada during the 1960s, there was a brief period of sedation, which directly resulted from some significant budgetary issues.[14] These academic libraries were faced with cost issues relating to the recently developed service of interlibrary lending and the high costs of periodicals on acquisition budgets, which affected overall acquisition budgeting and ultimately public collections.[14] Canadian academic libraries faced consistent problems relating to insufficient supplies and an overall lack of coordination among collections.[15]

Academic libraries within Canada might not have flourished or continued to be strengthened without the help of outside organizations. The Ontario Council of University Libraries (OCUL) was established in 1967 to promote unity among Canadian academic libraries.[16] The Ontario College and University Library Association (OCULA) is attached to the Ontario Library Association (OLA) and is concerned with representing academic librarians regarding issues shared in the academic library setting.[17]

Europe[edit]

.jpg/220px-Interior%2C_National_Library_of_Finland%2C_2019_(02).jpg)

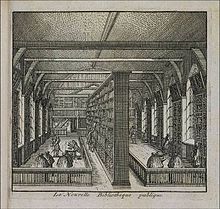

Some of the oldest examples of academic libraries in Europe include the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, the Library of Trinity College Dublin, and the Vilnius University Library in Lithuania.

European academic libraries are not especially dissimilar to American academic libraries overall. However, there do exist significant operative variances. First, many libraries do not have open stacks like American academic libraries do, which can also apply to an institution's general collections. Second, although some utilize a classification system similar to or based upon the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) used in the United States, it is not uncommon for European libraries to organize their collections through their own systems [18]

Modern academic libraries[edit]

Academic libraries have transformed in the 21st century to focus less on physical collection development, information access, and digital resources. Today's academic libraries typically provide access to subscription-based online resources, including research databases and ebook collections, in addition to physical books and journals. Academic libraries also offer space for students to work and study, in groups or individually, on "silent floors" and reference and research help services, sometimes including virtual reference services.[19][20] Some academic libraries lend out technology such as video cameras, iPads, and calculators. Many academic libraries have remodeled to reflect this changing focus as learning commons. Academic libraries and learning commons often house tutoring, writing centers, and other academic services.

A major focus of modern academic libraries is information literacy instruction, with most American academic libraries employing a person or department of people dedicated primarily to instruction.[21] Many academic institutions offer faculty status to librarians, and librarians are often expected to publish research in their field. Academic librarian positions in the United States usually require an MLIS degree from an ALA-accredited institution.[22] The Association of College and Research Libraries is the largest academic library organization in the United States.

See also[edit]

- Academic journal

- Internet search engines and libraries

- Shadow library

- Research library

- Research Libraries Group

- Research Libraries UK

- Library assessment

- Trends in library usage

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ a b c Curzon, Susan; Jennie Quinonez-Skinner (9 September 2009). Academic Libraries. pp. 11–22. doi:10.1081/E-ELIS3-120044525. ISBN 978-0-8493-9712-7. Retrieved 10 September 2013 – via Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences.

- ^ Pezzi, Bryan (2000). Massachusetts. Weigl Publishers. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-930954-35-9.

- ^ "Årsberetning 2015" (PDF) (in Danish). 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ Westbrook, Danielle Watters; Chua, Kristen. "Facts and Figures – UC Libraries". UC Libraries. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ "Nalanda—the lost beacon of knowledge". The Times of India. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Budd, John M. (1998). The Academic Library: Its Context, Its Purpose, and Its Operation. Englewood, Colorado: Libraries Unlimited. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-1-56308-457-7.

- ^ McCabe, Gerard; Ruth J. Person (1995). Academic Libraries: Their Rationale and Role in American Higher Education. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-313-28597-4.

- ^ a b Budd (1998), p. 34

- ^ McCabe (1995), pp. 1-3.

- ^ a b c d Beckman, M.; Dahms, M.; Lorne, B. (2010). "Libraries". Archived from the original on 14 September 2012.

- ^ Downs, R. B. (1967). Resources of Canadian academic and research libraries. Ottawa, ON.: Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada. pp. 9.

- ^ Downs, R. B. (1967). Resources of Canadian academic and research libraries. Ottawa, ON.: Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada. pp. 93.

- ^ Downs, R. B. (1967). Resources of Canadian academic and research libraries. Ottawa, ON.: Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada. pp. 4.

- ^ a b University research libraries: Report of the consultative group on university research libraries. Ottawa, ON: The Canada Council. 1978. p. 4.

- ^ University research libraries: Report of the consultative group on university research libraries. Ottawa, ON: The Canada Council. 1978. p. 2.

- ^ "A History of Collaboration". Ontario Council of University Libraries. 2011. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Ontario Library Association (n.d.). "About OCULA". Archived from the original on 6 December 2011.

- ^ "Library Resources Outside the U.S." Brown University Library. 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ "Changing Roles of Academic and Research Libraries". Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL). 30 May 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ "3D Tour of 5th Floor (silent floor) of USF Libraries Tampa," University of South Florida Libraries Digital Heritage and Humanities Collection (accessed 22 August 2021).

- ^ Research Planning and Review Committee, ACRL (5 June 2018). "2018 top trends in academic libraries: A review of the trends and issues affecting academic libraries in higher education" (PDF). College & Research Libraries News. 79 (6): 286. doi:10.5860/crln.79.6.286.

- ^ "Academic Libraries". Education & Careers. American Library Association. 21 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

Further reading[edit]

- Bazillion, Richard J. & Braun, Connie (1995) Academic Libraries as High-tech Gateways: a guide to design and space decisions. Chicago: American Library Association ISBN 0838906567

- --do.-- --do.-- 2nd ed. --do.-- 2001 ISBN 083890792X

- Jürgen Beyer, « Comparer les bibliothèques universitaires », Arbido newsletter 2012:8

- Ellsworth, Ralph E. (1973) Academic library buildings: a guide to architectural issues and solutions 530 pp. Boulder: Associated University Press

- Giustini, Dean (2011, 3 May) Canadian academic libraries' use of social media, 2011 update [Web log post].

- Hamlin, Arthur T. (1981). The University Library in the United States: Its Origins and Development. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812277951

- Hunt, C. J. (1993) "Academic library planning in the United Kingdom", in: British Journal of Academic Librarianship; vol. 8 (1993), pp. 3–16

- Shiflett, Orvin Lee (1981). Origins of American Academic Librarianship. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Pub. Corp. ISBN 9780893910822

- Taylor, Sue, ed. (1995) Building libraries for the information age: based on the proceedings of a symposium on The Future of Higher Educational Libraries at the King's Manor, York 11–12 April 1994. York: Institute of Advanced Architectural Studies, University of York ISBN 0-904761-49-5

- Letzter, Jonathan (March 2023). "The architecture of academic libraries in Israel: Knowledge and prestige". The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 49 (2): 102645. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102645. S2CID 253900804.